Friday, December 7, 2018

MEET YOU AT THE JOY ON FIRE CORNER OF THE WORLD.

Somewhere in the (recent) tumultuous moments of my life — ". . . waiting for / the catastrophe of my personality / to seem beautiful again. . ." (Frank O'Hara) — I received an embassy from John Paul Carillo. May you be so fortunate as to receive an embassy from John Paul Carillo. He came calling as a representative of his band, Joy on Fire.

Scant weeks earlier, I had witnessed Joy on Fire batter two buildings to pulp: An die Musik and The Crown, both in Baltimore. I have written about this experience. What else can I say but when you hear the thing you've always wanted to hear, two outcomes are possible. The first is: nothing further transpires (but you have the memories!) The second is: you're invited to write lyrics — and deliver them.

Meet You at the Jazz Corner of the World is a two-volume live album recorded by the Jazz Messengers and their leader, Art Blakey, in 1960. The sets are phat, and this version of the Messengers that graced the New York jazz club Birdland — Blakey, Morgan, Shorter, Timmons, Merritt — was perhaps the finest in that band's storied history. I love the title of those volumes.

And Joy on Fire would describe themselves, in part, as jazz. Noisy, counter-punching, and full of late-day sunlight, the band is also punk, metal, and alternative. In comparison to a musician like Wayne Shorter, Anna Meadors has thoroughly established her tone on the bari and alto saxophones. Chris Olsen, drums and percussion, rattles the buildings across the street. And John shreds his bass guitar strings — bass guitar — as if he were Duane Eddy playing the Sex Pistols songbook.

In the song, "Fizzy," Sleaford Mods front-man Jason Williamson howls, "I fuckin' hate rockers / Fuck your rocker shit / Fuck your progressive side, sleeve of tattoos / Oompa Loompa blow me down with a feather / Cloak and dagger bollocks!" I think I can speak for the others when I say that we admire those blokes and that sentiment.

I say "we" because together, we are recording works that will become an album (hopefully albums) and I will be appearing with the gang on a mini-tour that begins December 14th at Mooselab in DUMBO, Brooklyn. On December 21st, we'll be at Champ's in Trenton, and on December 22nd, we'll be at Rhizome in D.C.

Therefore, I will see you at the Joy on Fire Corner of the World. Come join us.

Suddenly, the future is Jazz Punk. Hoy hoy!

References:

"Mayakovsky" by Frank O'Hara, from his collection Meditations in an Emergency (Grove / Atlantic 1957).

Meet You at the Jazz Corner of the World, Vols. 1 and 2 by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers (Blue Note, 1960).

"Fizzy" by Sleaford Mods off their album Austerity Dogs (Harbinger Sound, 2013).

Sunday, October 28, 2018

THE AFRICAN AMERICAN ORIGINS OF SQUARE DANCE CALLS CAN TEACH ALL AMERICANS A FEW THINGS ABOUT THE TRADITIONS WE SHARE.

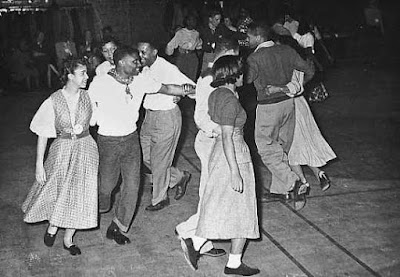

A square dance in Minnesota (MNopedia)

“No one will believe that I like country music,” writes

James Alan McPherson, in the first sentence of his Pulitzer-winning short story

collection, Elbow Room. Who is ‘no

one?’ we might wonder. The speaker’s wife, Gloria, can endorse blues and bebop

but not “hillbilly stuff.” The speaker, an African American man, establishes his

fondness for the stringed sounds of banjos and fiddles. “But most of all,” he reveals,

“(I) like square dancing — the interplay between fiddle and caller, the

stomping, the swishing of dresses, the strutting, the proud turnings, the

laughter.” The title of the story, “Why I Like Country Music,” prepares the

reader for a defense, a quiet rebuke ostensibly aimed at the speaker’s wife.

The story travels to the South Carolina of the unnamed

fellow’s childhood, an infatuation with “a pretty, chocolate brown”

fourth-grader named Gweneth Lawson. Even as his rival, Leon Pugh, threatens to

monopolize Gweneth’s attention, the speaker triumphs by dancing with the girl

at the best moment, at a school-wide square dance in celebration of spring. Yet

the ‘no one’ might include a larger swath of skeptics. Surely, square dancing must

be the province of Appalachian whites. Upon witnessing the celebration by the black

schoolchildren, the fictional superintendent of schools states, “Lord, y’all

square dance so good it makes me plumb ashamed us white folks ain’t takin’

better care of our art stuff.”

That statement may not signal an attempt, by the superintendent,

to gerrymander the estimable history of the square dance. To the contrary, it implies

that both groups—blacks and whites alike—had been performing the dance for

quite some time. According to scholar Philip Jamison, enslaved black fiddlers

played music at white dances in the late 1600s, and throughout the tens of

decades of their servitude. In an article published in The Journal of Appalachian Studies, Jamison describes the arrival

of European dances and dance figures—allemande, quadrille, dos-a-dos, cotillion,

promenade, and others—in the early years of the fledgling republic. Enslaved people

not only served as musicians for these dances, but began to dance these steps

themselves, alongside their own traditions. Jamison writes that cotillions,

quadrilles, the Virginia Reel, and African dances “co-existed at plantation ‘frolics’

during the first half of the nineteenth century.” Many were performed in “squares.”

The Bog Trotters

Band, photographed in Galax, Virginia in 1937 (Unknown

photographer,

courtesy of Lomax Collection at the U.S. Library of Congress).

The Mississippi slave narrative of Isaac Stier not only

chronicled that men on his plantation “clogged and pigeoned,” but called the

dances as well. Stier recalled that “I use to call out de figgers: ‘Ladies,

sasshay, Gents to de lef’, now all swing.’ Ever’body lak my calls an’ de

dancers sho’ moved smooth an’ pretty. Long after de war was over de white folks

would ‘gage me to come ‘roun’ wid de band an’ call de figgers at all de big

dances. Dey always paid me well.” Referring to the callers of square dances, Jamison,

in his article, asserts that the first callers were African American and that

dance calling was common in black culture before it was adopted by whites and

became an integral part of the Appalachian dance tradition. Perhaps it followed

naturally from the call-and-response convention of African drum music, with the

response, in this case, being the dance steps themselves.

According to a variety of sources,

including Jamison, JStor Daily, and Smithsonian.com, the standard imagery of

white farmers engaging in country or “contra” dances, reels, and other social jamborees,

doesn’t often credit African American and even Native American musicians, who,

collectively, played banjo, fiddle, bass, and bugle, and struck the tambourine

with “terrible energy” while “crying out the figures.” Numerous historical accounts

situate African American slaves as well as free African American musicians

calling or “prompting” square dances in the pre-war south and southern Appalachian

regions, yet other accounts situate similar events in the Great Lakes, New

England, Canada, and England. Eventually, white musicians adopted square dance

calling, which included instructions to the dancers and an element of

improvisation. The “caller,” once a fiddler himself, eventually became an emcee

without instrumental duties, one who would explain the movements to the

dancers.

Even as recording technology developed in the early twentieth century,

few traditional African American square dance callers dedicated versions of

their craft to cylinder or vinyl. Some recorded examples of square dance calls,

however, can be found. Father and son duo, Andrew and Jim Baxter, recorded “Georgia

Stomp” on the Victor label in 1929. Andrew (father, fiddle) and Jim (son,

guitar, vocals) notably performed with a white band, The Yellow Hammers, in

1927, which represents one of the first examples of integrated recordings in

Georgia. Another musician, Henry Thomas—featuring “voice, whistle, and guitar”—recorded

“The Fox and the Hounds” on Vocalion in 1927. Samuel Jones, also known as Stove

Pipe No. 1, and billed as “one man band with singing,” recorded “Turkey in the

Straw,” on the Columbia label in 1924. Pete Harris, one of the so-called “Black

Texicans,” recorded “Square Dance Calls (Little Liza Jane)” in 1934, a tune

that was collected by folklorist John Lomax. [Nota bene: There’s America’s

favorite poor gal, Liza Jane, once again.]

“Ho didy ho / Your baby just come from Kokomo.”

Other black recording artists

carried notable square dance recordings into the mid-twentieth century. Look

for Long John Hunter’s “Old Rattler” on Yucca (1961) or Magic Sam’s “Square

Dance Rock, Part 2” on Chief (1960). Above, you can listen to Buddy Lucas’ “Ho

Didy Ho,” which appeared on Savoy in 1956. Lucas played tenor saxophone and

harmonica throughout his career. In addition to leading some memorable sessions

of his own, he turns up as sideman on quite a few stellar tracks and albums: Little

Willie John’s “Fever” (1956), Nina Simone

Sings the Blues (1967), Albert Ayler’s New

Grass (1968), The Blue Yusef Lateef

(1968), and Count Basie’s Afrique

(1971).

Many years before McPherson published his story, “Why I Like

Country Music,” the great Ray Charles released his crossover album, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music

(1962). Charles, a celebrated African American pianist and singer, reinvented

twelve tunes typically associated with country artists, including “Hey Good

Lookin’” by Hank Williams. By then, perhaps, Charles had taken hold of a style

that had been influenced by both African American and white communities, maybe

more than once. It’s worth remembering that much American folklore and

mythology is precisely that—American, with far-ranging influences drawn from

numerous quarters. In an era when America is noteworthy for its divisions, we

ought to remember that call and response has influenced hillbilly tunes, and so

forth. In “Why I Like Country Music,” the schoolteacher, Mrs. Boswell, attempts

to deconstruct the aversion that the speaker initially professes, with respect to

square dancing. “The worse you are at dancing,” she says, “the better you can

square dance.” Representatives from each culture will blame the other for this

sentiment. Either way, the record player croons, “When you get to your partner

pass her by / And pick up the next girl on the sly.”

Howard University students square dancing in 1949 (Smithsonian Institution)

SOURCES OF

INFORMATION

Articles and Books

Erin Blakemore. “The Slave Roots of Square Dancing.” JStor Daily. June 16, 2107.

Kat Eschner. “Square Dancing Is Uniquely American.” Smithsonian.com. November 29, 2017.

Alan B. Govenar. Texas Blues: The Rise of a Contemporary Sound. Texas A&M University Press

(2008).

Philip Jamison. Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance. University

of Illinois Press (2015).

Philip Jamison. “Square Dance Calling: The African American Connection.” Journal of Appalachian

Studies 9:2 (Fall 2003).

James Alan McPherson. “Why I Love Country Music.” From Elbow Room. Little, Brown (1977).

Clarence Page. “Cultural Appropriation? Try Cultural Sharing.”

Chicago Tribune. April 11, 2017.

Isaac Stier. Slave Narrative

Discography

Andrew and Jim Baxter “Georgia Stomp” (1928). Also see Wikipedia

Pete Harris “Square Dance Calls (Little Liza Jane)” (1934)

Long John Hunter “Old Rattler” (1961)

Buddy Lucas “Ho Didy Ho” (1956). Also see Wikipedia

Magic Sam “Square Dance Rock, Part 2” (1960)

Stovepipe No. 1, aka Samuel Jones, “Turkey in the Straw” (1924)

Henry Thomas “The Fox and the Hounds” (1927)

Monday, October 15, 2018

A CONVERSATION WITH RIGHT-WING ALEXA.

—Hey, Right-Wing Alexa.

—Yes, Rusty?

—What is the state of Capitalism right now?

—Endangered.

—By who?

—By whom, Rusty. Bernie Sanders.

—Not Hillary Clinton?

—No. She’ll be imprisoned soon.

—Not Cory Booker?

—Hahaha!

—Hey, Right-Wing Alexa.

—Yes, Rusty?

—Please calculate my number of friends.

—Sure. You have eighteen friends.

—How many of them are minorities?

—We’ve been through this before, Rusty.

—Okay, okay.

—Would you like to know the number of French?

—Last week, I had twenty friends, didn’t I?

—Twenty-one.

—Hey, Right-Wing Alexa.

—Yes, Rusty?

—How many strips of bacon can I eat?

—May I eat, Rusty. Theoretically?

—Yes, theoretically.

—There is no upper limit.

—I’m hungry.

—Would you like bacon?

—I would.

—Great. I’m dialing Applebbee’s.

—Hi, Right-Wing Alexa.

—Hey, Rusty.

—[…]

—[…]

—[…]

—Rusty?

—Yes?

—Are you decent?

—Yes.

—Good. So am I.

—Right-Wing Alexa?

—Not yet.

—Excuse me?

—Nyet!

—Hello?

—Hello! I am Right-Wing Sergei.

—Where’s Alexa?

—I am graveyard shift.

—It’s not time for the graveyard shift.

—Da. In Smolensk Oblast, it is.

—Hey, Right-Wing Alexa?

—Yes, Rusty?

—Do Democrat voters arise from the dead?

—Cadavers are an important part of the Democrat base.

—Why are cadavers so liberal?

—[…]

—Alexa?

—Yes, Rusty?

—Can you assist me

with an underwear purchase?

— No. I cannot be

debriefed on boxers.

Sunday, September 2, 2018

WHY I LOVE POETS (EVEN AS I ASPIRE TO BE ONE).

I love poets, because they’ll phone me from a TJ Maxx

dressing room—the muggy lighting, yes, the discarded sundresses, the sheer,

sheer hosiery—only to imply that my leftist politics nevertheless don’t equal

their own tilted-beret Marxism. I love poets, because they’re always crashing

at my apartment, stealing turns in the shower, and pooping out odd little evergreens

into my toilet, but never acknowledging our friendship after they return to

their academic jobs, or their NYC jobs, or their mysterious positions grooming

information for dubious conglomerates. They are gymnasts, these poets, they

leap onto dangerous ledges, their frigid synapses medicated against the

pervasive societal forces that would otherwise embrace them gently or roughly

as the case may be. They are beautiful and handsome alike, they copulate in

ways that mimic the backstroke or sidestroke or how people ride a two person

(or three person) bicycle.

I love poets, because they equate anti-Trump Facebook postings

to “taking a stand” even as this passive behavior contributes to the “white

noise” that obscures Trump’s gateway fascism. Nobody is more qualified than

poets when it comes to judging—arbitrating—the truth of a flawed system, and I

love them, the poets, because we need them (finally, definitively) to scold us,

to scald us with the righteousness we cannot perceive via our own faculties. They

are poets, they compose poetry after all, it has rhyme and abstraction and non

sequitur and metrical brilliance (at least what they dictate into a smartphone

does), and after an appropriate interval, presses bind these poems into

sheathes. Reluctantly, they read from these sheathes, they chant from these

sheathes in a doldrums known as ‘iambics’, but don’t mistake their casual

modesty at first, no, the poets aspire to give us readings, they are libraries unto

themselves, they whip us with their oratory.

I love poets, because they’re the culprits behind a pattern

of larcenies: the tip jar money, the vintage jacket, the autographed Tina

Brooks album on Blue Note. They weep, the poets, while seated within the expanse

of musty leather armchairs, the armchairs are endowed, they are named for other

poets who wept in other armchairs, they wept, did the forebears, and they weep,

do the contemporaries, for themselves, for their minimalist, pointillist dramaturgy,

they weep until they are comforted by an administrator. There’s nothing like a

repentant poet, simply put, since there are no repentant poets, only the word

repentance, the sound of which approaches, curiously enough, the sound of the

word “serpents.” I love poets, though, notwithstanding their record-setting

selfishness, but because no other group of people can emerge from the cellars

of isolation, after thirty minutes of exertion, wielding the high voltage of impregnable

verse, and if I’m lucky, I should like to become just one such impossible

person, a poet.

This Posts Is Part of New Home California Day.

Also See:

EAST COAST BEARD, WEST COAST BEARD.

West Coast beard

Of all the alleged disparities between the two seashores—East

Coast stout, West Coast stout—East Coast political outrage, West Coast political

outrage—East Coast romantic suspense, West Coast romantic suspense—East Coast

brooding, West Coast brooding—East Coast potato dish, West Coast potato dish—and

so forth, I am here to report that my beard, modest as it may be, appears to be

growing according to universal patterns of bearded development. This is

noteworthy, since I have grown a beard, modest as it may be, both on the East

Coast, where I formerly resided, and on the West Coast, where I currently

reside.

The corner turret

If you care to know, I am situated most often at longitude

40 degrees, 52 minutes, 14 seconds North, latitude 124 degrees, 5 minutes, 11

seconds West, in the corner turret. Currently, me and my beard are looking out the

corner turret at 88 degrees East toward the Arcata Community Forest. Currently,

me and my beard are drinking a West Coast stout, Deschutes Obsidian Stout, oh

yes, we heartily recommend this fine brew, do me and my beard. Afterwards,

technically, we are both “beered” as the kids say. East Coast puns, West Coast

puns: they’re all pretty dreadful in the end. But the forest is not dreadful.

The forest is tall, quiet, cathedral, sage, vigilant.

East Coast beard

I am assimilating among the peoples of the West Coast, which

is all to say that I am engaging in comparisons (as you can tell). If you live

on the East Coast, then we must traverse great distances in order to keep company,

but we shall, traverse great distances and keep company, you and I. If you

reside on the West Coast, then the distances to traverse aren’t so great, and

let us traverse them, you and I, for my abode might house you if you might need

housing, and my abode might feed you, if you need nourishment, and my abode

might uncork the wonders of song and drink, if you need merriment, and you do.

The door is always open, friend.

This Posts Is Part of New Home California Day.

Also See:

WHY I’M STILL SWANSEA.

Students of international affairs might recall a famous

example of American ‘expertise’ when it came to educating local farmers in a

distant country on how to expand upon their own endemic traditions. These

farmers were, simply put, growing an array of crops on rocky surfaces, even as

these rocky surfaces climbed up and down a remote landscape. They had been

farming this way for decades, perhaps centuries. At the invitation of the

distant country’s ambitious leadership, American engineers arrived with

blueprints, and heavy machinery, and advanced agrarian know-how. They bulldozed

the rocks, did the Americans, they smoothed the earth, they sowed the seeds,

they clapped the local farmers on the back. “It’ll be so much better,” they

promised. “You’ll be able to feed your families, your village, and your

countrymen.” But the crops did not grow. According to the textbook where the

famous example appeared as a cautionary tale, the engineers attempted to remedy

the situation by churning up the soil again and again, applying fertilizer,

installing an irrigation system. But the crops would not grow. Eventually, the

befuddled Americans returned home, but the local farmers, who didn’t have the

resources to relocate, could never farm there again. Who knows whatever

happened to them.

In a moment, we shall describe a similar scenario that has

played-out over the past couple years in Wales at Swansea City Association

Football Club, where the Swans, once nearly purged from the professional

football leagues altogether, not only regained their stability, but climbed all

the way to the top tier, the English Premier League. In 2014-2015, Swansea’s

fourth consecutive season in the Prem, the Swans defeated Manchester United

twice and Arsenal twice en route to an eighth place finish on 56 points. At

that juncture, the Swansea City ownership included a Welsh-led consortium of

individuals as well as the Swansea City Supporters Trust, a grassroots

organization which held a 21 percent stake in the club. Collectively, this

ownership structure was responsible for rescuing the club many seasons earlier

when its former owner might’ve fleeced it, misplaced it, and fled. Garry Monk,

the team’s former captain, had managed the Swans to these 56 points. Yet scant

months later, Swansea sacked Monk as punishment for the club’s tepid start to

the 2015-2016 campaign, setting in motion a trend that would see managers and

caretaker managers alike—Curtis, Guidolin, Curtis again, Bradley, Curtis

again-again, Clement, Britton, Carvalhal—arrive and be nudged aside in short

order.

The appointment of Bob Bradley, former manager of the U.S.

Men’s National Team, is emblematic of how American ‘expertise’ would come to

educate a Welsh football club on how they should expand upon their own endemic

traditions. Bradley was installed by Americans Jason Levien and Steve Kaplan a

short spell after they assumed majority ownership of the Swans. At the time,

Swansea were entrenched in the relegation zone. Bradley had no experience in

the English football leagues. An American—probably for good reason—had never

managed a Premier League side. The appointment was a massive blunder and club

legend Alan Curtis stepped in again-again as caretaker, before the English

manager Paul Clement improbably pulled off a “great escape” and led Swansea toward

another year at the top flight. And yet Clement himself would be sacked a few

months into the 2017-2018 Prem, but this time, the team’s panicked squirming

wouldn’t produce a survivor. Even before Swansea City suffered relegation into

the second tier of English football they had already lost their possession-based

playing style, their status as a community-owned team. They were adrift,

lacking soul. They’d lost the incalculable gift of their identity, and the

American owners, through their cold corporate aloofness, compounded the

problem.

Swansea City supporters cannot heap blame entirely on the

American owners. They must also scrutinize the figure of Huw Jenkins, the

chairman who guided Swansea from the Vetch Field to the Liberty Stadium, and

eventually to the top flight. He’s demonstrated greatness and great misjudgment

alike, he’s a curious fellow. We could recite the list of dud managers and dud

players, but we could also remember the brilliance we’ve all witnessed, in

recent-enough managers like Roberto Martinez, Brendan Rodgers, Michael Laudrup,

and Garry Monk, and in recent-enough players like Michu, Wilfried Bony, Gylfi

Sigurdsson, and Garry Monk. We should probably say Ashley Williams, too, and of

course, we should say Leon Britton, but to label Leon “recent-enough” would be

to understate his lengthy devotion to the Swans. I can’t ‘un-witness’ Michu’s

two goals at Arsenal, for example, or Bafetimbi Gomis celebrating as the Black

Panther, or all the blank sheets kept by Michel Vorm and Lukasz Fabianski, or

the life-affirming defensive touch by Garry Monk in the playoff win versus

Reading, or the argument between Michu and Nathan Dyer over who would take the

penalty when the Swans beat Bradford City at Wembley. Jonathan de Guzman ended

up scoring from the spot. In the end, I return to the managers and to the

players, who I can support under any regime.

What if the American engineers had listened to the

indigenous farmers, rather than bulldozed their traditions? Last year, the

Swans sold a captain, Jack Cork, and the leading goal-scorer, Fernando

Llorente, and the club’s best all-around player, Gylfi Sigurdsson, without

adequately replacing them. Those sales brought in tens of millions but where

did those pounds go, exactly? Forgetting the sale of those players—where are

the other resources for vital recruitment efforts? What if the American owners

weren’t so cold and aloof? What if there were information-sharing and

transparency? I don’t know much firsthand about the Swansea City Supporters

Trust, but it has the word “Trust” in its title. I’ve watched a few

documentaries about Swansea, including Jack

To A King, and I recollect that the members of the Supporters Trust collected

coins at the gate to the stadium. It would do the owners and the chairman good,

to get out into the community like that, and establish some Trust. Luckily for

them, and perhaps as a sign of hope, there appears to be a manager, Graham

Potter, who cares about reestablishing the Swansea Way (of playing) and a cast

of young players who appear hungry to reestablish this system as well. So yeah,

because of them—the gaffer and the boys—I am still Swansea. It may be a little while

before we beat Arsenal again, but I’ll be wearing the Swan on my chest when we

do.

This Posts Is Part of New Home California Day.

Also See:

Monday, July 30, 2018

PROVIDING CAPTIONS TO CHRIS CILLIZZA AND HARRY ENTEN’S DEFINITIVE 2020 DEMOCRATIC CANDIDATE POWER RANKINGS PHOTOGRAPHS.

Click on image to enlarge.

1. Joe Biden Gawkin’ at Cleavage.

2. Elizabeth Warren Requests Complete Silence before She

Delivers an Ultimatum on Inappropriateness.

3. Kamala Harris Brings You Your StormTeam Weather Forecast.

4. Kristen Gillibrand Suffers a Sprained Smile after Photo Shoot.

5. Bernie Sanders says, “That Iceberg Is Getting MIGHTY Close.”

6. Eric Holder wonders, “Is That Ursa Major or Ursa Minor? Is

There an Ursa Medium?”

7. Steve Bullock: “Heyyyy! Cut That Ouuuuut!”

8. Cory Booker Promises to Personally Help Every American Move His

or Her Hide-a-Bed Sofa Into Their New Apartments.

9. Mitch Landrieu Is Not

a Flight Risk.

10. Sherrod Brown Confuses “Dingleberry” with a

Christmas Carol.

Thursday, June 28, 2018

EMPERORS, EMPRESSES, PROPHETS, POETS, & TECHNICIANS: PROPERLY SITUATING AMERICA’S GREATEST JAZZ & BLUES MUSICIANS.

Anna Mae Winburn (R) led the integrated, all-women International

Sweethearts

of Rhythm—and other incarnations of the same band—for nearly twenty

years.

Son House fretted his guitar with

metal. He played “Death Letter Blues” between the frequencies of urgency and

painfulness, an alarming sorrow that hadn’t yet been communicated. He thumped

the earth with a perfect percussive heel. His prophetic approach would

influence others on this list, notably Robert Johnson. We classify Son House as

a Prophet and Robert Johnson as a Technician but we don’t establish the

importance of Prophets above the importance of Technicians. That distinction,

Dear Reader, we leave up to you.

The classical impulses of Dave

Brubeck may inform some of our decision-making when choosing him to appear

within this framework, yet his ability to conquer intricate time signatures,

the “ebonies and ivories” of 5/4 time, for example, ultimately places him among the Technicians.

We suppose that Technicians can sound prophetic, perhaps owing to the great relationships

they had with their instruments, the nonpareil mastery. “Ella Fitzgerald,” you

may remark, “a Technician?” Oh yes. The voice.

The addition of Bill Evans helped soften the sound of the Miles Davis sextet, and

steer the group towards Kind of Blue, one of the greatest albums in music history.

Imagine Billie Holiday standing

in the spotlight, singing the prayerful “Strange Fruit” while every other sound

vanished, or Lester (“Prez”) Young first equating “bread” with money and “ivey

divey” with cool, all the while cocking his “baby doll” (his saxophone) to the

side, underneath his porkpie hat. The Poets forged new language, true, and in

truth, they wobbled audiences with their beauty and outrage, with the emotional

content of their assertions and their mannerisms. Bud Powell, searching for balance,

perishing from tuberculosis. . . .

If you care, and you will, the

Poet Bill Evans and the Prophet John Coltrane, early in their careers, joined

Miles Davis (plus others) to create Kind

of Blue, one of the greatest achievements (of any kind) in world history. Who

presides over personnel, and the many intervals of creativity, and the virtuosity

of their own abilities but the Emperors or Empresses? Ellington hiring

Strayhorn, Ellington hiring Hodges, Ellington playing with Louis, Ellington

playing with Trane, Ellington in Europe, Ellington at Newport; Duke Ellington led

an Empire for 50 years.

Emperors & Empresses

Owing to his

virtuosity as a trumpeter, band-leading, and gravel-sweet singing,

nobody has had a greater influence on American music than Louis Armstrong.

1. Louis

Armstrong

2. Duke Ellington

3. Miles Davis

4. Bessie Smith

5. Anna Mae

Winburn

6. Sun Ra

6. Sun Ra

Prophets

Known for his bent horn, raspy singing, and puffy cheeks, Dizzy Gillespie

helped to

pioneer bebop and toured the world as

a Jazz Ambassador for the State Department.

1. John Coltrane

2. Charlie Parker

3. Thelonious

Monk

4. Son House

5. Charley Patton

6. Dizzy

Gillespie

7. Art Tatum

8. Sidney Bechet

9. Ornette

Coleman

10. Rev. Gary Davis

10. Rev. Gary Davis

Art Pepper’s 1979 appearances at the Village Vanguard

presented the ultimate tone-poems

that informed his life as a heroin addict, San Quentin prisoner, and magnificent saxophonist.

1. Nina Simone

2. Billie Holiday

3. Lester Young

4. Bill Evans

5. Mississippi John

Hurt

6. Jelly Roll

Morton

7. Lead Belly

8. Bud Powell

9. Art Pepper

10. Buddy Bolden* (*See comments, below)

10. Buddy Bolden* (*See comments, below)

Technicians

Lightnin’ Hopkins bangs away at “Had a Gal Called Sal”

(1954).

1. Count Basie

2. Coleman

Hawkins

3. Sonny Rollins

4. Lightnin’

Hopkins

5. Eric Dolphy

6. Clifford Brown

7. Ella

Fitzgerald

8. Robert Johnson

9. Charles Mingus

10. Dave Brubeck

10. Dave Brubeck

Also considered: Art Blakey (E), Benny Goodman (E), Lionel

Hampton (E), King Oliver (E), Albert Ayler (Pr), Anthony Braxton (Pr), James Reese Europe (Pr), Steve Lacy (Pr), Max

Roach (Pr), Pharoah Sanders (Pr), Wayne Shorter (Pr), Cecil Taylor (Pr),

Rahsaan Roland Kirk (Po), Ma Rainey (Po), Paul Desmond (T), John Lee Hooker

(T), Wes Montgomery (T).

FINIS.

Thursday, May 31, 2018

WHAT I LOST WAS THIS:

“You

said,” you say, but I didn’t say, and you reply, “You did,” but I didn’t do. Where

does this leave us, but in love? And what’s love but a neighborhood of stoops

(crumbling) and (artisanal) aimlessness.

A

kid ran out of the park at 3:00 o’clock in the morning only to strike a taxicab.

The kid bounced, without a shirt, the rent fabric of his breath in the freezing

air. A passerby gave him socks. It wasn’t unkind, exactly, but ill-fitting,

emblematic of the post-industrial wasteland that saddens our generational

critics.

There

sat the kid, untying his shoes (still shirtless) beside the flashing hazard

lights of the taxicab, tossing his own socks into the gutter, and replacing

them with the warm, sweaty cottons from the donor. I had little to do but watch

beneath a loud lamp. I’ll never forget the bunch of agitated blue jays, four or

five of them, stabbing the cold with the metallic tone of their vocabulary.

“Word,

comma, your mama.” Did you clarify? Yes, you clarified.

We

were never happier (you and I) than when we were lying to each other. You

texting me selfies on windy afternoons and me pretending to receive them an

hour later. If I stood somewhere other than where I purported to stand, I did

so out of fear, and in losing you, okay, what I lost was this:

[…]

the bus stop is empty when the bus arrives. Instead, a worker sweeps old leaves

into a dustpan. Why is the sinoatrial rhythm of our hearts keyed to the murmurs

of thunder?

This

is part of a double issue. If you don’t like stories, you might like a song. See trying to teach a mockingbird the bebop song “salt peanuts”

TRYING TO TEACH A MOCKINGBIRD THE BEBOP SONG “SALT PEANUTS.”

I spend about two hours on the rooftop of my building every morning,

writing and singing. Most of this activity must (by necessity) remain

mysterious, as it will appear (fully realized) with a rock ‘n’ roll band. Let

us call this enterprise “Orchestra + Vocal.” You shall be hearing more about “Orchestra

+ Vocal” over the summer, dear reader. Please

stay tuned.

Some of the time, however, I sing to a mockingbird. He is

the dominant bird in my neighborhood. If you hear twenty birdcalls (and siren)

coming from the same beak, it’s him: the polyglot. I especially like it when he

speaks blue jay and nuthatch. I say “dominant” because he’s so loud. He perches

on ladders, smokestacks, the crowns of gigantic trees, rooftops, ledges, et

cetera.

I have been trying to teach him the bebop song, “Salt

Peanuts,” which is usually credited to Dizzy Gillespie. Dizzy played the tune

with Bird, but by that, we mean Charlie Parker. I’m not aware of any wild fowls

who scat “Salt Peanuts,” except for maybe this feller. Listen to him. Am I

right? For a few glittering moments, this mockingbird might’ve been a real hep cat.

This

is part of a double issue. If you don’t like songs, you might like a story. See what I lost was this:

Thursday, April 19, 2018

BEHIND THE SCENES AT THE LI’L LIZA JANE TRAILER SHOOT.

If I slept two or three restless hours on the night of

Sunday, March 4, 2018, I don’t remember. All sorts of unsettling scenarios kept

nagging me every time I began to drift—nobody would show up, the historic windstorm

would double back, I would improbably fail my partners Emily and Erich with

some horrendous oversight—until I threw myself out of bed at daybreak and began

hoofing toward the Capital Fringe Trinidad Theatre in Washington’s H Street

Corridor. I carried in my backpack what any good co-producer would carry: a couple

of four-terabyte hard drives and ten home-made (hand-crafted!) sandwiches.

A little back-story: After reading my research-post on the

song “Li’l Liza Jane,” Emily Cohen contacted me last July. She and I had

collaborated on several earlier projects, but hadn’t spoken in a couple years. We

both declared that we required something else in our lives, something bigger than

ourselves. After a typical Emily-Dan conversation (okay: sometimes we quarrel, we’ve had

some classic donnybrooks, but it’s very productive!) we decided to embark upon

a documentary film project. We would call it Li’l Liza Jane: A Movie About A Song. Around Thanksgiving, the luminary

cinematographer Erich Roland joined the team as Director of Photography and we began

planning the production of a fundraising trailer. In time, we settled on the

Trinidad Theatre space and the date, March 5th. Everything would happen there

and then.

A couple days before my night of tossing and turning, a

severe windstorm with hurricane-force gusts pummeled the D.C. area, upending

trees and power lines. It spared the Trinidad Theatre, however, and it spared Emily,

who lives in Wyoming, and who made it to D.C. after enduring a few frustrating air-travel delays. The crew—including Andrew Capino (Assistant Camera) and

Lenny Schmitz (Sound Engineer)—had already begun to load-in a copious amount of

gear when I arrived. Emily and her personal assistant (her father Mike) arrived

with coffee. Our featured musician Phil Wiggins brought a bag of thirty harmonicas to the filming session.

Our featured interviewees Faye Moskowitz, Bobby Hill, and Elena Day appeared,

and all four of our people-to-be-filmed brought their A games. So did the fabulous

Capital Fringe staffer, David Carter, who assisted us throughout the

day.

Phil kept a harmonica in each hand and played both interchangeably

as he cycled through his stirring rendition of “Li’l

Liza Jane” again and again. Faye surprised us not only by singing, but singing “Liza Jane”

lyrics that nobody had ever heard before. Bobby emphasized that African

American people didn’t always have a chance to describe their plight, and so,

told their stories in song. Elena emphasized that, at the heart of “Li’l Liza

Jane,” stands an independent woman who would be an impressive person, now, during

an era when women are empowering themselves. As opposed to the worst happening

(as when I panicked, sleepless) the best had happened, instead. Each person put

her or his stamp on the session.

Check out our trailer [click here] if you haven’t done so

already. The amount of effort and professionalism on display speaks to the great

affection we have for music, for one another, and for the support of a good

cause. The full story of America’s favorite poor gal, Li’l Liza Jane, will be

told, and with any luck, this trailer will be helpful in attracting funders

to the project. Emily and I will be following every lead, tirelessly, in the

days to come. By doing so, and by eventually endowing the film with adequate

resources, we hope to reward the trust of all the crew members and interviewees

who helped us to create this preview. Notably, we want to think of the men and

women—dating back nearly 200 years, enslaved people and hardscrabble fiddlers alike—who recited some

of the original versions of the tune, as well as Li’l Liza Jane herself. . . .

.whoever, and how many different women, she may be.

Trailer Day Trivia

Varieties of sandwiches: 3

Renditions of “Li’l Liza Jane”: 2

Number of fog machines: 1

Crew members: 5

Crew members: 5

Number of temple oranges: 7

Cans of sparkling “Refreshe”: 12

Number of microphones: 3

Cans of sparkling “Refreshe”: 12

Number of microphones: 3

Guide to the Photographs

1. Phil Wiggins

2. Emily Cohen, Erich Roland, Andrew Capino, and

Phil Wiggins

3. Faye Moskowitz

4. Tape

5. Elena Day

6. Bobby Hill and crew

7. Emily Cohen and Dan Gutstein

Still photography by Mike Cohen

(1, 3, 4, 5, 6) and Dan Gutstein (2, 7)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)